My passion lies in projects contributing to sustainable community economic development. I believe that Rotary International is uniquely positioned to change the world through sustainable economic development. We have the people, the energy, and the resources, and now we need the focus!

I have been convinced for years that if money could solve this tragedy of poverty, it would have been solved a long time ago. Yesterday, 33,000 people died and they died needlessly. Today, 33,000 people will die from things that can be prevented; tomorrow the same thing will happen, and the day after that. These people, many of them children under the age of five, die a miserable death from starvation, malnutrition, contaminated water, and lack of medical intervention.

The citizens of the United States alone invested over $8 billion in humanitarian aid. That is money right out of our pockets given to humanitarian aid projects. This is not to mention the billions of volunteer hours that many of us have invested in helping others. Still, 33,000 people will die needlessly today. I submit to you, that is not a very good return on our investment. How can we secure our investment of our time, talent, and treasure?

Today I am going to follow the words of Gandhi when he said: “Don’t tell people what to do; tell them a story and they will know what to do.”

I will share my story of an education sponsorship project in Bali, Indonesia — how it changed from an unsustainable project to one that eventually brought dignity and self-respect to the villagers through sustainability.

I was encouraged to get involved in a project that would send impoverished children living in a rural village in Indonesia to school. When I first visited this village, it was clear that these were either truly forgotten or unnoticed or ignored people.

The impoverished people in Indonesia were no strangers to me, and they were not faceless. I was introduced to this village by a Rotary club in Indonesia while on a Group Study Exchange as the team leader.

When we visited impoverished villages, mothers of the village asked me to hold their babies. These children were very different from any other children I had seen before. Most of them were malnourished, with bloated little bellies; some were all skin and bone; many were naked and had chunks of hair missing, all due to malnutrition and starvation.

I asked my counterpart, Freddy Subiyanto, “Why do these mothers want me to hold their babies?” He told me it gave them hope. I was confused and asked, “Hope for what?” He did not know exactly what. “They probably think that you are a mother, too, and hope that something will change now that you have seen, and there will be help for their suffering children.”

I don’t remember anyone ever looking at me with hope before. It was a very uncomfortable feeling, and I felt a huge responsibility to do something, but I had no idea what. It felt overwhelming.

Later, I was given a UNICEF report submitted to the United Nations stating that the children of Indonesia were in the worst possible circumstance of children in all of Asia, due to malnutrition and lack of education.

Rotarians in Indonesia informed me that, for $60 per year, we could send a child to school, paying for books, supplies, uniforms, one pair of shoes, one cup of rice a day, a small portion of meat two times a week, and a daily nutritional supplement. Who in this room would not give $60 for such a good cause of educating impoverished children? As many projects go, the population we intended to serve grew, because every time we visited the village, we could not bear to see the children who desperately wanted to go to school but had no funding.

Within a few years, the people we were hitting up for donations in the States — mostly my fellow Rotarians to include The Rotary Foundation — were supporting every child in that village to go to school. That meant 1,200 children at $60 per child per year, for the annual fundraising goal of $72,000.

The villagers were happy. The donors back home were happy when they saw the pictures every year of the children they were supporting. I felt empowered; it gave me an adrenaline rush just to think of the positive impact for these children, for future generations, the donors, and eventually the world.

My third year of returning to the remote village, we were approached by Nyoman, an impoverished farmer, walking up from his rice field. He was speaking with Freddy and asked if we really wanted to help them.

Nyoman told Freddy that three of his children were on our school list. He said if we really wanted to help, he needed a water buffalo. I assured him we did not “do” water buffaloes, only scholastic sponsorships.

He told Freddy that if he had a water buffalo, he could triple his rice production and have enough money to send his own children to school.

Later, I asked Freddy the cost of a water buffalo. He said about $250, and it would be as valuable as a John Deere tractor to a farmer in the States.

I thought about Nyoman and the water buffalo on the long trip home from Indonesia. I thought, if we did this, for the first time, the number of children in need of our educational sponsorships would be shrinking rather than snowballing.

How would I convince my donors I needed a water buffalo? That seemed too complicated, with too many questions.

Then my family asked what I wanted for Christmas. I announced: “I want a water buffalo!” That did not go without questions either, but as strange as it felt, they gift-wrapped a box with $250 in it, all in $1 bills, and gave it to me for Christmas, along with a card telling me “not to spend it all in one place.” But I did! I wired the money to Freddy, and he was going to make it all happen.

The next spring, back in Indonesia, I was making my usual visit to the village when Nyoman rushed across the terraced rice field, greeting me. He took my hand and introduced his water buffalo — named Ibu Marilyn! How cool is that!

The women of the village were inspired by Nyoman and asked for funds to purchase 20 piglets to start a business. They intended to breed and raise pigs, sell some to neighboring villages for profit, eat some and have better nourishment for their families, and use the manure in the rice fields.

I have thought long and hard about the education project in Indonesia and how I helped design, and promoted, an unsustainable plan that robbed others of dignity and pride and built a dependency on us.

What was the message my annual visit was giving the villagers? “You need us to get your children an education? We don’t have enough confidence in you to make it happen on your own?”

What about their dignity? Where was their voice? Who had the power in that message?

I could have, should have, been asking questions and listening to their ideas. We can’t save the world, but we certainly can change the world through opportunity. Searching for sustainable programs: My personal odyssey continues!

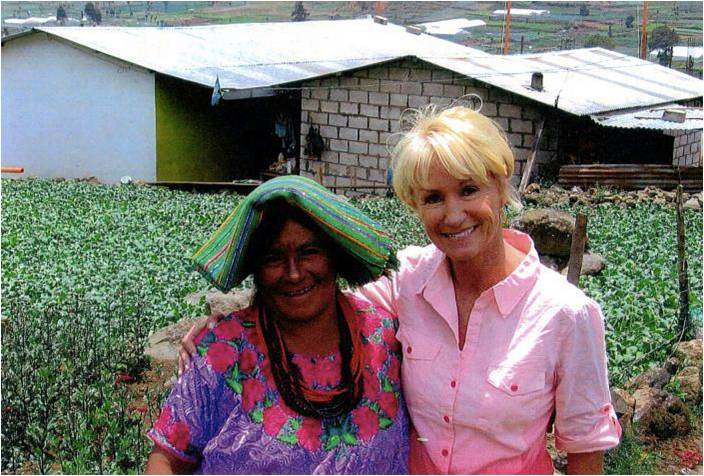

This was a totally different humanitarian-aid world, and it represented what people can accomplish when provided an opportunity. These were smiling people who were proud to look me straight in the eye and tell me about their business. They are innovative, fiercely hardworking, resilient entrepreneurs benefiting from an opportunity created through microloans.

I had been involved in the western highlands of Guatemala, evaluating projects. Traveling with a local Mayan translator, we were going to see a rural microloan borrower, Shirley the tortilla maker. The translator introduced me and said: “This is Marilyn. She helped get the money for your first microloan.” A tiny woman, about this tall, looked me straight in the eye and said, “Yes! And I have paid you back!” I was so proud of her, that she had enough self-esteem to own her success.

Shirley did not even know how to count a year earlier. She learned by counting coffee beans. Now, she pulled out her accounting notebook and, in her own writing, showed me how much it cost for her to make a tortilla and how many she had to sell to break even. It was amazing!

Not all projects intending a sustainable impact are successful. It would be wonderful if all sustainable economic development projects were as simple as buying a water buffalo or 20 piglets and maybe some hens for eggs. In reality, not even the project in Indonesia was that simple, even after we got on the sustainable track.

The village women did not know how to care for piglets or how to run a business, how to determine the cost of their goods sold, how to market, how to increase the capacity of their business or, for that matter, how to harvest a pig.

Local Rotarians mentored the new entrepreneurs, brought in educational systems and literacy programs for the entrepreneurs. The Rotary clubs in the U.S. provided financial resources, but the local Rotary clubs had to provide all the due diligence to ensure success.

Rotarians can provide opportunities for people to help themselves. How can we secure the return on our investment? We have got to give serious time, treasure, and talent to sustainable projects. We have to ask ourselves the difficult but important question: Are we leaving people with respect, dignity, and opportunity, or have we created a dependency?

Remember this: We have the people, the energy, and the resources to change the world with sustainable programs. You, as leaders in Rotary, have the power and the influence to propel change!

“Be the change that you hope to see in the world!” — Gandhi